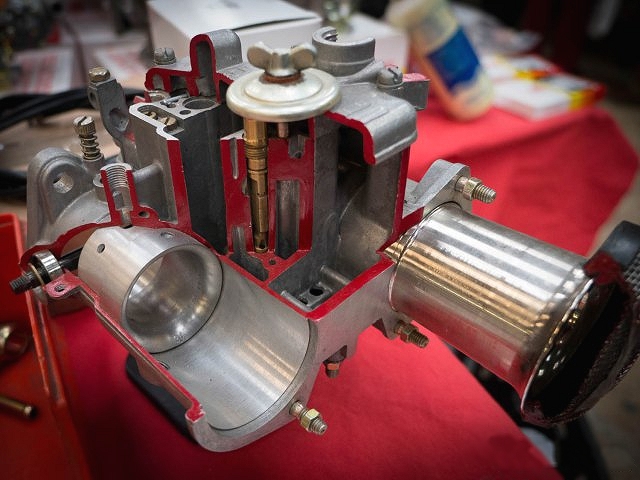

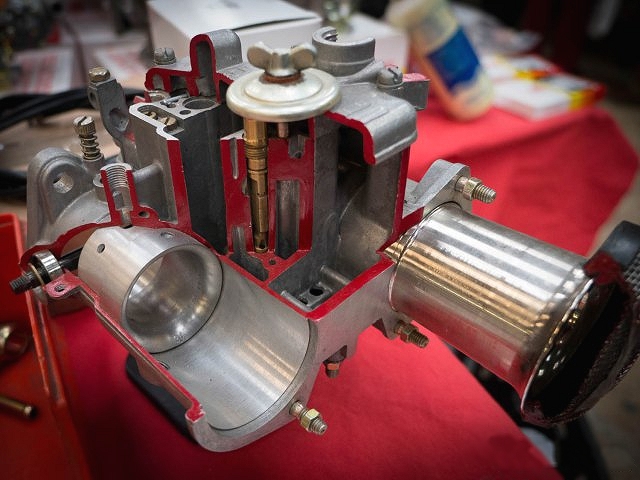

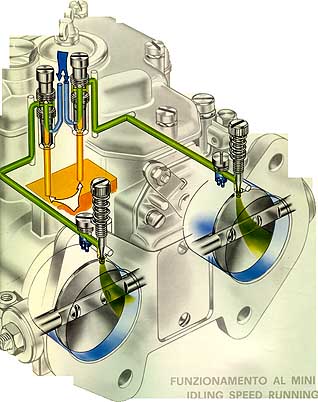

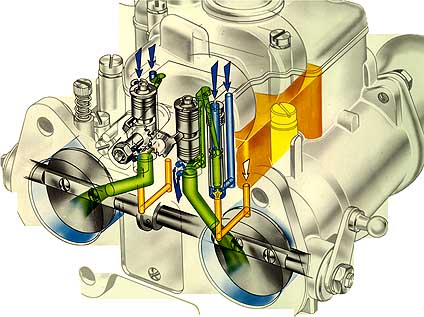

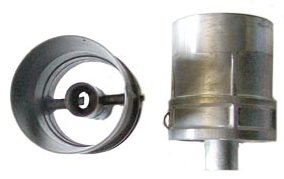

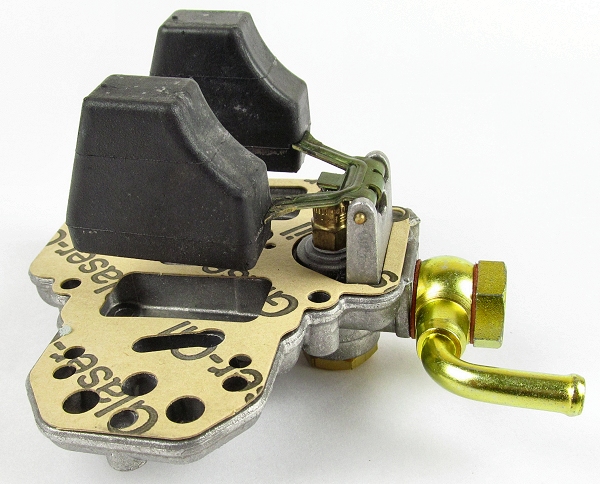

Figure 0. Weber DCOE Cut Away

By: Philip Pilgrim

Weber DCOE Carburetor Reference: Theory,

Configuration, Tuning, Modifications, & Reference Documents

(for Datsun 240z, 260z, & 280z Owners)

Thanks to Weber Expert Dave from

CarbParts.eu for

continued technical oversight

Figure 0. Weber DCOE Cut Away

By: Philip Pilgrim

Contents:

1. Introduction

2. Theory of Operation

3. Circuit Drawings

4. Components

5. Tuning

6. Rebuilding

7. Modifications

8. Racing

9. Reference Documents

1. Introduction:

More Complex than an SU:

The SU carbs on our early Datsun 240z's & 260z's are

constant velocity carbs that have only one circuit that meters air and

distributes fuel. It is a simple design with a clever automatic method that

exploits a movable piston and needle valve. This one circuit works across the

full rpm range and full load range from idle to wide-open-throttle (WOT).

In contrast, the Weber DCOE is more complex in that

it has five separate circuits whose components are fixed. These circuits are

optimized for different parts of the rpm range and load range. These circuits

interact and overlap at the transitions in rpm and load. Unlike the SU that uses

a big clunky piston, the DCOE's metering of fuel is based upon small precisely

machined brass jets that are well fixed inside the carb. They are very capable

of working in in high g-force racing conditions and a wide selection of jets and

other parts allow for the DCOE carb to be optimized for nearly any engine size

and application.

Enjoy this Refreshment Before Continuing to

Read:

Remember: The pistons are trying to pull air into the engine

like lungs breathing. Your foot on the accelerator pedal only lets air into the

engine (It is not a "gas" pedal but rather an "air" pedal). Your foot is

controlling how much air enters the engine by opening and closing a throttle

valve. The carburetor's job is simply to mix the correct quantity of fuel with

the air you let pass through it so that the engine can burn it correctly. The

carb has to correctly add the right amount of fuel for all situations: cold,

hot, travelling over violent bumps, when pulling high g-forces:

turning/braking/accelerating, with engine vibrations, when idling, when

racing, when cruising through town or along a highway, when operating high in

the mountains or at sea level.

Why this Page Exists:

Having tamed the DCOE beast, I will attempt to pass

along my findings to help you confidently do the same but with fewer obstacles. In retrospect, DCOE carbs

are fairly easy to understand and easy to set up. The challenge is to have

someone reduce the beasties to the simple elements for which they actually are....

thus this page.

It's Simple:

Weber DCOE carbs have always carried an air of a

mystery in their operations and tuning. They have been with us for many years,

(DCO's since the early 1930's). Still, after 85 years, it is as if there is some sort of magic associated

with DCOE's and with anyone who can tune them. This is false. They are simply

lumps of aluminum composed of a handful of sub-sections (circuits) that can all

add fuel at different times during the operation of a vehicle.

Each of the circuits can be "tuned" by replacing components (typically changing

items with different sized holes to let more air or fuel into each circuit...or

to reduce air or fuel in each circuit).

The correct interworking of all circuits together is the ultimate goal of a

properly tuned DCOE. However, one must be careful as the circuits overlap one another; it is possible to

sometimes fix an over-fuel situation in one circuit by under-fuelling in another.

Beware of the Internet: (but not this page)

Often many of us go down the path of seeking ideal

configuration advice on the internet. This is difficult to do and

usually leads one down the wrong path (loss of performance, running too rich,

etc.). The problem is that most proclaimed configurations are from un-vetted

sources promoting certain settings and component vales that are not accurately

verified and most often, subjective. Furthermore, if the engine with the

promoted settings is not the same as yours then the settings are moot. A good

example of this problem is that most proclaimed "ideal" settings do not include

fuel level. This one critical factor will greatly skew how all of the circuits

work. If your fuel level is different from the person's promoting the ideal

settings, then you are wasting your time copying their settings. In fact this

problem happened to me. When I first started to tune DCOE's for a 240z, I

thoroughly read a very long DCOE configuration thread on a website forum called

HybridZ. I wrongly assumed most of the posts were accurate and from experienced

DCOE tuners. It was a waste of time (Out of curiosity I just looked and the

continuing thread and it is now over 800 posts of the blind leading the blind!).

Their settings did not work for me and after I paid my dues in learning the DCOE

circuits and the DCOE circuit interactions, I can now see how most of the

HybridZ DCOE content is incorrect and I can advise not to try to mimic the

settings and advice of others. If the "internet" DCOE settings do not state the

fuel level and DCOE version along with engine displacement, manifold, tuning,

etc. then they are not useful.

Having stated the least favourable way to configure

DCOE's, the ultimate way to configure and optimize DCOE's is to set up the

engine on a dynamometer and tune for power or fuel efficiency, or whatever your

goal is. This has been done many times and ideal values achieved.... however

this is usually expensive and done on race motors by race teams for maximum

performance and least risk of damage in contingencies. Most of us do not have

race motors let alone race so again, their optimized DCOE configurations are

usually not the same as ours.

Since most of us have street machines and most of us

do not have engine dynos, we are forced to tune by simply driving.

The first step to tuning Weber DCOE's is to understand

how they work and their various circuits.

2. Theory of Operation

This section is an attempt simplify and present DCOE functioning so that you can

quickly grasp the basic concepts.

It is a fictional guess at how Mr. Weber would have developed a DCOE design

step-by-step. It should help in demystifying the DCOE:

The Ideal:

The simplest carburetor design would be a tube to flow

air with a source of gasoline spraying in the centre of the tube. This would

provide even distribution and symmetrical mixing of air and fuel at the highest

velocity point of the tube.

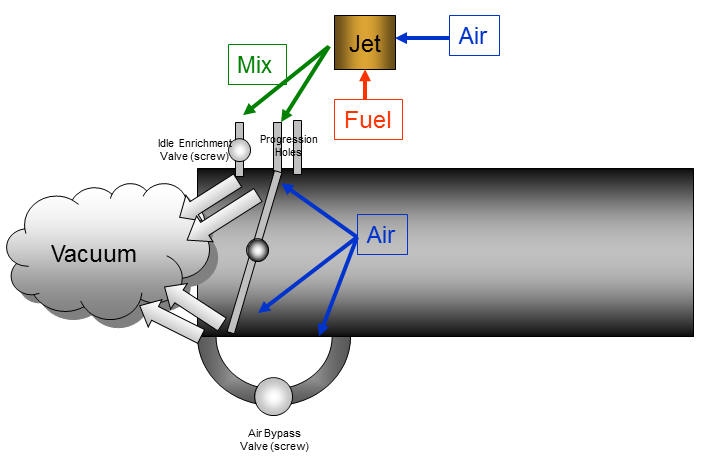

Figure 1. Ideal Carb

Approaching the Ideal:

The DCOE Main Circuit

The Weber DCOE side-draft carb, commonly used on the

Datsun 240z, 260z, & 280z, is basically just a tube with a fuel nozzle in the

mid-stream of the air path.

In Figure 2, the DCOE Main circuit is shown. It is very much like the Ideal Carb

above.

Figure 2. DCOE Main Circuit

Unfortunately another part was

required.... the Throttle Valve. It is connected to the accelerator pedal and

controls the amount of fuel and air drawn into the engine. Its location was

chosen to be downstream from the fuel nozzle as the manifold vacuum on the motor

side of this valve would otherwise suck the fuel from the fuel nozzle when the

throttle valve was closed. The main drawback of the throttle valve location

being downstream is that it still blocks the air flow when open and, fuel sprays

over it and can also be deposited on it. In addition to a simple tube with a

fuel nozzle design, Weber shaped the tube so that it was narrowest where the

fuel was drawn into the air stream by using the Venturi principal. This promoted

fuel draw and fuel distribution.

Here is a nice video showing the DCOE main circuit flowing water on a flow

bench:

Video 1. DCOE Main Circuit "Wet Flow"

The DCOE carb has many swappable parts for the main circuit to configure it for

different engine sizes and applications. These will be discussed later. For the

present, just focus on the theory of operation.

Side Note: It is interesting how this simple tube

and nozzle design is nearly identical to a modern high performance fuel injected

individual throttle body (ITB) manifold architecture. Modern fuel systems

actively squirt fuel in precisely metered quantities into the air stream where

as carbs must draw the fuel through Venturi vacuum created by the air stream.

The above Main Circuit design is only marginally optimal for being an Ideal

Carb. It works OK in the middle to wide open throttle range yet it fails

completely at idle and works poorly at WOT.

Here are the two main deficiencies of this simple

design:

1. At lowest rpms (Idling) when the throttle

valve is nearly closed, there is not enough air flow over the main nozzle to

draw fuel. (Lean)

2. At higher rpms when the throttle valve is

moderately to fully opened, the air fuel mixture becomes too rich as too much

fuel is drawn from the main nozzle. (Rich)

Reality and Corrective Actions In the Design:

Adding the Idle Circuit and the Emulsion Tube

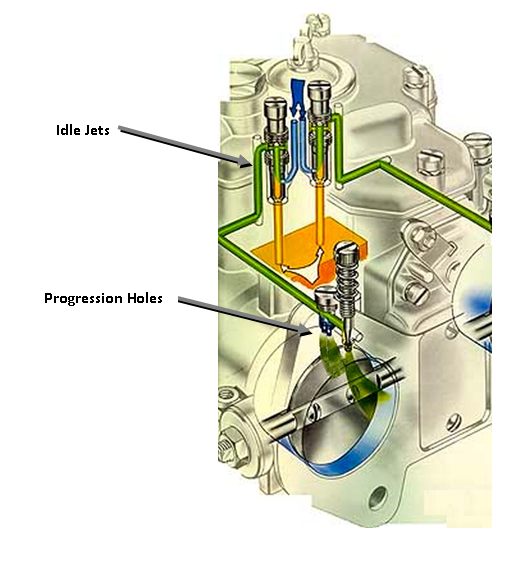

The way the DCOE addresses the above

two problems of Main Circuit fuel flow at both ends of the RPM spectrum is:

The DCOE Idle Circuit:

To address idling lean, as the main nozzle is situated nowhere near the high

velocity air flow, a separate second circuit is added: the Idle Circuit (Figure

3). It is simply a variable hole (needle valve) on the high vacuum downstream

side of the throttle valve. This needle valve independently controls the amount

of pre-mixed fuel and air (mixed upstream and not shown for simplicity) to flow

past the throttle valve and feed the engine when the throttle valve is nearly

closed (and the main circuit was not functioning due to low air flow). The

simple one circuit carburetor example now becomes two circuits (Main and Idle).

As with the DCOE Main Circuit, the DCOE Idle Circuit has configurable parts that

can be swapped to adapt it to different engine sizes and applications. Details

will be shown later.

Figure 3. DCOE Idle Circuit

The Emulsion Tube:

To address the need to lean the mixture in the Main Circuit as the throttle

valve approaches "Wide Open Throttle valve" (WOT), a “fuel/air mixing tower” is

added. It is a tube with holes in it and it is called an “emulsion tube”. Air

and Fuel mixing takes place in and around this tower before the fuel/air

emulsion is drawn

out of the assembly. Fuel enters the tower at the bottom of the well and air

enters from the top. As the fuel demand increases approaching WOT, the fuel

level in the tower & well lowers and in turn, exposes more air holes thus mixing

more air with the fuel. This ultimately leans the mixture (as required) in the

main circuit as more airflow through the carb occurs.

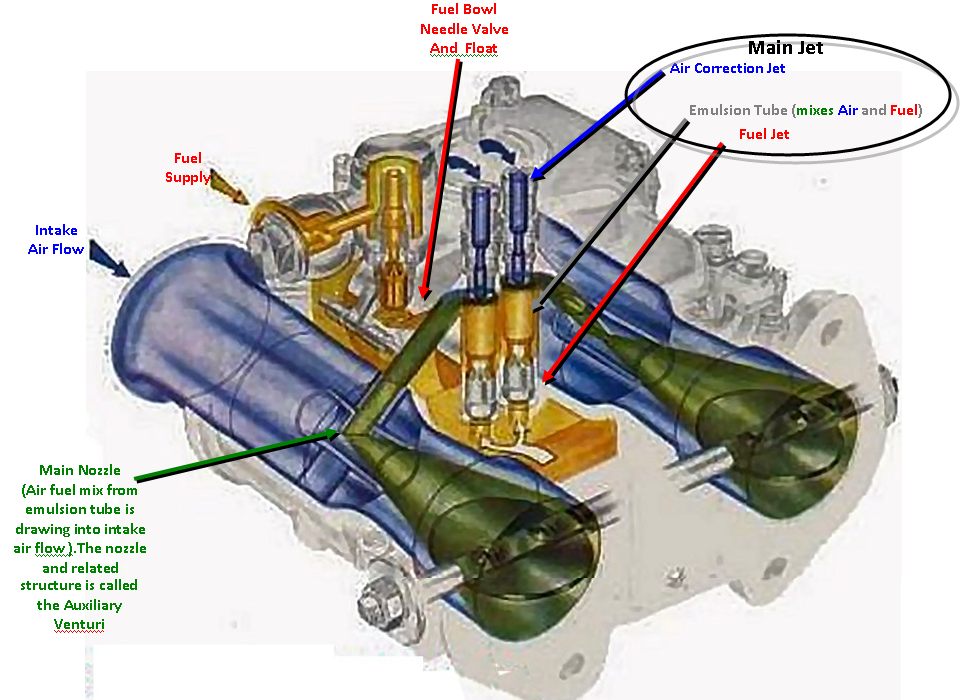

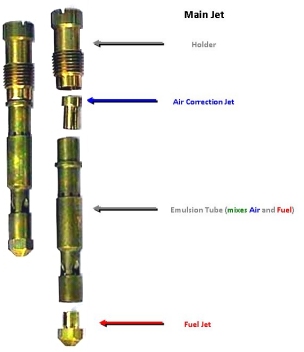

Here is a picture of a DCOE emulsion tube and a video of it in action mixing air

with fuel as a stationary car is rev'd to WOT (with no load). Details of the emulsion tube will be shared

later in this page. Currently the main point to take-away is that the emulsion

tube and well prevents the Main Circuit from going too rich at WOT by mixing air

with the fuel.

Figure 3. DCOE Emulsion Tube

Video 2. DCOE Emulsion Tube Mixing Air with Fuel for Main Circuit

Note: The fuel level is too high to start and it creeps higher.

Video 3. DCOE Main Circuit Operating

Note: The emulsion tube is not optimal or the fuel level is too high as pure gas

dribbles out when the main circuit is first activated. This common problem will

be addressed in the tuning section.

To recap: The DCOE has been

shown to be at least a 2 circuit carb design:

One being the Idle Circuit and the second being the

Main Circuit.

....But how to switch from one circuit to the other circuit slowly and quickly?

Dealing with the Transitions: Adding

the Progression Circuit and the Acceleration Circuit

The DCOE Progression Circuit (for slow

transitions from Idle Circuit to Main Circuit):

As the throttle valve slowly opens, when transitioning

from the Idle Circuit to the Main Circuit, the air flow required to activate the

main circuit does not occur quick enough. This delay in the main circuit

starting causes a lean spot between Idle and Main. The solution is to simply add

more fuel holes near the throttle valve. These holes are drilled upstream of the

idle needle valve port. As the throttle valve is opened, it exposes each

successive hole to the manifold vacuum and air flow. In turn, (due to high

velocity air and manifold vacuum) it draws more mixed air/fuel from each

progression hole. For economy of design, the source of the air fuel used in the

Progression Circuit is simply a tap from the Idle Circuit.

Figure 4. DCOE Progression Circuit

It is important to note that

when cruising down the highway at constant speed, the throttle valve is usually

opened only part way between idle and WOT thus the Progression Circuit is

important for cruising performance (static) and when transitioning from idle

towards WOT (dynamic).

It is *very important* to note that the Progression

Circuit is fed fuel and air directly from a configurable part in the DCOE called

the Idle Jet. The only way to adjust the air and fuel in the progression circuit

is to swap the Idle Jet with others of different sizes or to raise and lower the

fuel level. In fact, to better understand the DCOE carburetor, renaming the

"Idle Jet" to the "Slow Progression & Cruise Jet" would be more intuitive. The

Idle Circuit is more or less dependent only on the Idle Enrichment Screw.

The Accelerator Pump Circuit (for fast

transitions from Idle to Main):

If the throttle valve opens quickly (when

transitioning from the Idle Circuit to the Main Circuit) the Progression Circuit

above does not have enough time to operate as the airflow is suddenly

distributed across the whole carb throat rather than focused up near the roof

and progression holes. This sudden bust of air and delay in the main circuit

starting causes a momentary lean spot between idle and main. Most Weber

aficionados call this the "gasp". The solution is to

actively add more fuel by using a one-shot-squirt-gun-like pump that is

activated on a quick throttle opening (hammering the gas pedal). The Accelerator

Circuit design also had a clever feature where slow throttle valve openings do

not squirt additional fuel (to be shown in more detail further below).

The Accelerator Pump actively and forcefully squirts fuel into the air flow like

a fuel injector but it does so only for 1 shot.

As with the other circuits, The DCOE carb has swappable parts to configure the

accelerator circuit for how much fuel is squirt and for how long.

Figure 5. DCOE Accelerator Circuit

Video 4. DCOE Accelerator Pump "Squirting"

Video 5. DCO Main and Accelerator Pump (Too Rich)

Summary to this Point:

A Weber DCOE side draft carb used on many Datsuns now

has at least four independent "circuits":

1. Idle Circuit (used at idle)

2. Main Circuit (used between cruising and WOT)

3. Progression Circuit (used to aid in

slow rpm

transitions from Idle Circuit to Main Circuit and to provide most fuel at

cruising).

4. Acceleration Circuit (used to aid in

fast

rpm transitions from Idle Circuit to Main Circuit).

Figure 6 is a graph showing the three passive

circuits (Idle, Progression and Main) and how they overlap across the engine

RPM's. This will be an important point to note when tuning the DCOE carb.

The Acceleration circuit is not shown as it is active and only squirts when the

accelerator pedal is pushed quickly.

Figure 6. Overlap of DCOE Circuits and RPM

The Starter Circuit

(for cold starting):

The final circuit (the fifth) in the Weber DCOE is the Starter Circuit. It is an

optional circuit that is not present on many DCOE's. It is not needed for race

applications and it is not useful for most climates. In fact it can be a

nuisance if it malfunctions. Finally, for cold weather starting, simply pressing

the accelerator pedal quickly a few times will squirt fuel into the intake

manifold and prime the cylinders prior to ignition. This priming is a good

substitute for the Starter Circuit.

Well I guess I should say something about the Starter Circuit! It is not at all

like a Choke. It is very complicated and is much like a little carb within a big

carb. It has its own fuel and air passages and components independent of the

other circuits. When active, it feeds fuel downstream from the throttle

plate so it is exposed to manifold vacuum (just like the idle enrichment screw).

As with the other DCOE circuits, the

Starter Circuit has many swappable parts to enable configuring it for many

different engines.

It is confusing as to why this circuit is so complex and configurable for automotive applications,

however, Weber carbs are used for many applications and it may be for cold

weather vehicles or cold weather marine applications.

Figure 6. DCOE Starter Circuit

The Fuel Bowl:

Although the fuel bowl is not a "Circuit" in the Weber DCOE. It is common to all

circuits and deserves special mention:

Like most carbs, the Weber DCOE has a fuel bowl from which fuel is used for the

five circuits. Apart from the active Accelerator Circuit, the remaining

four circuits are passive and fuel is drawn from the fuel bowl through vacuum.

Both manifold vacuum and Venturi vacuum pull the fuel up from the fuel bowl.

The fuel level greatly affects how much fuel is drawn into each circuit for the

same amount of vacuum (air). The higher the fuel level fuel, the more of it will

be drawn and the richer the mixture becomes. Fuel level is critical for

correct running DCOE carbs. A high fuel level will bring the main

circuit in too early and over power the progression circuit to make cruise

"stinking rich". The high fuel level effectively hampers the correct functioning

of the emulsion tube by flooding the upper holes.

Like other DCOE parts, fuel bowl related components are configurable with

interchangeable parts to adapt to a variety of engines. br />

3. Circuit Drawings

This section contains drawings of Weber DCOE carbs and highlights the various

circuits.

Air & fuel passages and mixing is shown by colour. Air is blue and fuel is

yellow. Mixed air and fuel is green.

Idle Circuit Drawings

Figure 7. DCOE Idle Circuit Flow & Components

Figure 8. DCOE Idle Circuit

Flow

(Higher Resolution) Note the narrow-taper Idle Enrichment Screws.

Figure 9. DCOE Idle Circuit (Side View) Note the

wide-tapered Idle Enrichment Screw.

Figure 11. DCOE Idle Enrichment Hole

NNote that the Idle Enrichment

Hole is on manifold vacuum side of the throttle valve and is subjected to a

large pressure difference that pulls the air/fuel mixture from this hole. Some

air also flows past the throttle valve at idle to dilute this mixture.

![]()

Figure 12. DCOE Idle Enrichment Screws (Two common types shown above with different

tapers however at least six existed as part numbers end with: 1,3,11,23,56,58)

DDCOE Idle Enrichment Screws control how much fuel & air is fed to the engine at idle. At idle the Throttle Valve is opened just a crack so some additional air passes it and also feeds the engine at idle. The amount of fuel and air they provide is generally measured by how many turns out from full close they are set. Early DCOE Webers had a fat wide taper and permitted more flow at smaller turns, later model DCOE Webers are fitted with narrow tapered screws that are more accurate and require more turns to flow the same amount as their predecessors.

Figure 12a. DCOE Idle

Enrichment Hole/span>

Figure 13. DCOE Idle Circuit Jet & Holder

DCOE Idle Jets meter the amount of air and fuel mixed

and fed to the Idle Circuit & Progression Circuit. The Jets have a fuel inlet

hole at the bottom and air inlet holes on the sides. The mixture of air and fuel

is first pulled through four holes in the holder and then through a complex

winding set of passages in the carb body to reach the Idle Enrichment Hole and

to reach the Progression Holes. Idle jets are available in a wide selection. The

variables are:

1. diameter and depth of the internal cavity

2. diameter of the fuel inlet port

3. diameter and quantity of the air inlet ports

4. diameter of mixture exit port

Main Circuit Drawings

Figure 14. DCOE Main Circuit Flow & Components

Figure 15. DCOE Main Circuit Flow & Components (High Resolution)

Figure 16. DCOE Main Circuit (Side View) Note the inclusion of fuel leaking from

the Accelerator Circuit at WOT.

Video 6. Accelerator Pump Circuit "Leaking" at WOT

(look at the throttle plate at the end of the run to see the raw fuel leak

splash at the top)

Figure 17. DCOE Main Circuit (Front View Showing Venturi, Aux Venturi, & Emulsion Tube)

Fuel is pulled up through the well in which the Emulsion

Tube sits. The fuel travels up both inside and outside of the Emulsion Tube. As

it travels it mixes with air that enters the emulsion tube from the top. The

quantity, shape, location and diameter of holes drilled in the Emulsion Tube

along with its interior diameter and outer diameter affect the mix of the air

and fuel as the engine increases in RPM towards redline. The diameter of the

fuel port in the Main Jet (at bottom) and the diameter of the Air Corrector port

(at top) are also key components in how the emulsion tube works.

It is important to note that the Emulsion Tube only affects the fuel entering

the engine under high loads or high rpms when the main circuit is active. For

most street driving, it is not active. The Emulsion Tube type, Main Jet and Air

Corrector work together to meter the fuel as the rpms rise. They are typically

selected to prevent early WOT lower rpm range from being too rich or too lean

and to prevent the WOT upper rpm range from being too rich or too lean.

Figure 18. DCOE Main Circuit Emulsion Tube (Parts from bottom: Main Jet, E-Tube,

Air Corrector, Holder)

Figure 19. DCOE Main Circuit Venturi (left) and Aux Venturi 45DCOE (right)

The throat of a DCOE carb has two components along with

a Throttle Valve:

The Venturi (also known as a Choke), is simply a restriction to

reduce the maximum diameter of the throat

(choking it). The Venturi comes in a variety of diameters to help match the carb

to the engine. Smaller engines need less air and larger engines need more air.

The size of the venturi also controls the velocity of the air entering the

engine. Faster flow generally improves low-rpm torque but requires a

smaller diameter choke, higher rpm performance requires the most air flow and a

large diameter choke is usually best. As the main Venturi ultimately

controls the airflow through the carb, all circuits are affected as the flow of

air is what pulls the fuel out of them. Changing the Venturi will require

"re-jetting" (changing the idle jet, main jet & air corrector).

The Auxiliary Venturi is positioned in the centre of the carb

throat where the air velocity is greatest. The Main Circuit dispenses fuel

through it. The Aux. Venturi comes in a few sizes and shapes for tuning.

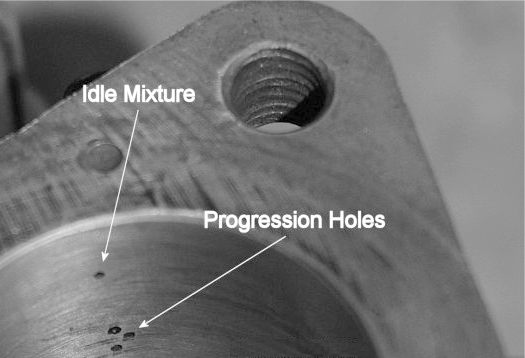

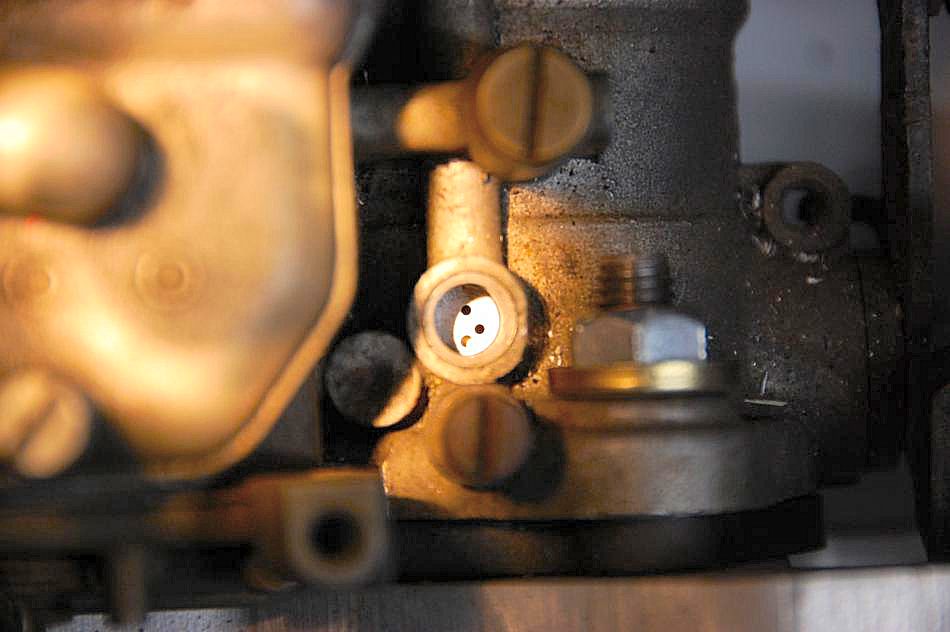

Progression Circuit

Drawings

Figure 20. DCOE Progression

Circuit

Figure 21. DCOE Progression

Circuit (Side View)

Figure 22. DCOE Progression

Holes

Figure 23. DCOE Progression

Holes (viewed from access port on top)

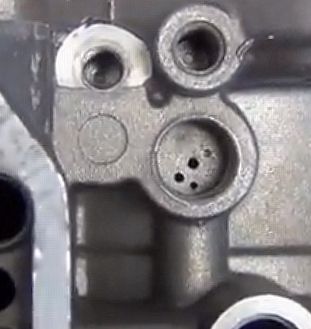

Progression holes can be

viewed from above by simply removing a threaded brass cap (Figure 23). (Note

that some early DCOE's have a non-removable cap so no inspections are possible). This

inspection is important for setting the throttle valve position at idle as it

should be at or behind the first progression hole. In this photo, you can see

that the throttle valve is blocking the first of the three progression holes. It

is a wee bit too far forward as it should only block~ 1/2 of the hole or less.

Getting the Throttle Valve set correctly is an important starting point for

tuning carbs. The design is such that the Progression Circuit should not be

activated until off idle. By having the Throttle Valve set too far forward

when tuning, one can incorrectly select jets that may partially work but the

Progression Circuit will be active at idle and the Main Circuit will come on

early. This will hamper the correct operation and make tuning more difficult

than necessary.

It is also worth noting that different 40DCOE carb bodies have different numbers

of progression holes (ranging from two to four with three being the common).

Size and location of holes also varies. For this reason it is critical

that for multi-carb applications, all carbs are of the same typo and preferably

from the same batch).

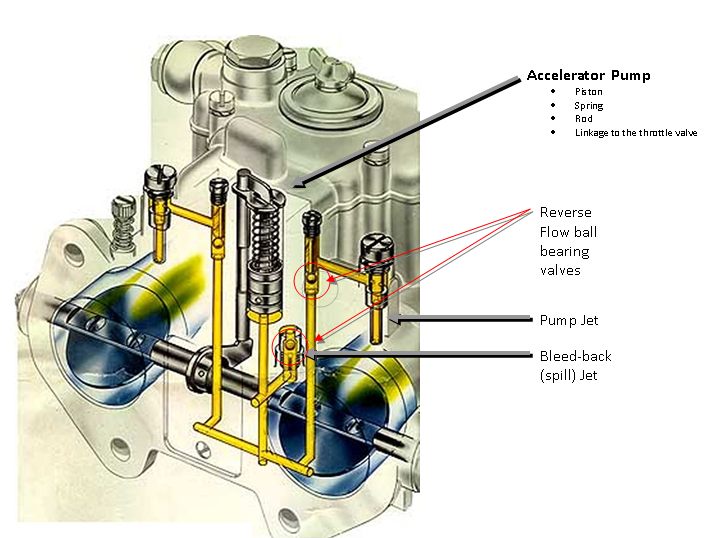

Accelerator Circuit Drawings

Figure 24. DCOE Accelerator

Circuit

Figure 25. DCOE Accelerator

Circuit (Side View)

Figure 26. DCOE Accelerator

Circuit (Side View)

The Accelerator Circuit pumps (squirts) fuel when the

accelerator pedal is pressed quickly. It does not squirt fuel when the

pedal is pressed slowly. Special passages and controlled leaks along with a

piston pump are the main components that circulate the fuel. As will other

DCOE circuits, many components are interchangeable with larger and smaller

orifices.

Key points to understand the functioning:

1. The Bleed-Back/Spill jets sit at the bottom of the

fuel bowl.

2. When the throttle valve is closed (idle), fuel

enters the Bleed-Back valve, flows past the ball bearing valve and fills the

pump chamber as the rod is pushing the piston up high in the pump chamber and

the spring compressed. Weights atop the two other ball bearing valves keep them

closed and prevents fuel from flowing out of the two jets.

3. When the throttle is opened quickly, the rod drops

and the spring pushes the piston down. This forces fuel backwards. The ball

bearing in the spill jet is forced upward and closes this valve preventing fuel

from back-flowing into the fuel bowl. The pressure also lifts the other two ball

bearings and corresponding weights (opening these valves) and allows the squirt

of fuel to shoot out each pump jet.

4. The diameter of the pump jet holes, the length of

the piston's excursion, and the spring tension affect how much fuel is squirt

and the time duration of the squirt.

5. When the throttle is opened slowly, the rod also

drops but the fuel squirts slowly back into the fuel bowl as the ball bearing

valve in the bleed-back/spill valve is designed to "bleed" on slow throttle

transitions. In fact the Progression Circuit is designed to be the key supplier

of fuel during slow throttle transitions...however some fuel will inevitably go

through the pump jets. Size of the bleed back valves, accelerator ball bearing

weights and piston spring pressure are the key factors in how "leaky" the pump

jets are in slow to medium transitions and also can be customized for normal

fast transition squirts.

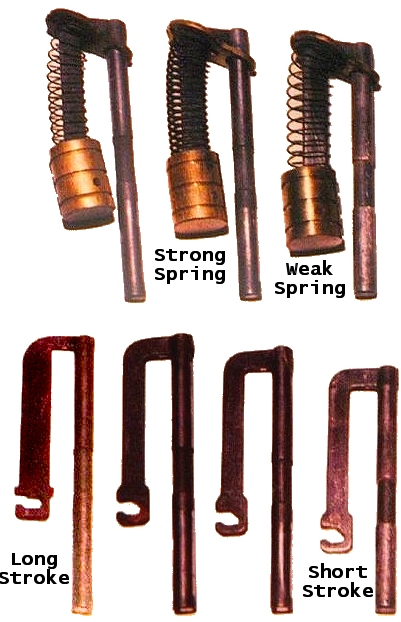

Accelerator pumps are composed of several components:

piston, rod, spring, and retainer:

Figure 27. DCOE Accelerator Pump Parts

Rods and springs can come in different sizes:

Figure 28. DCOE Accelerator Rod and Spring Selections.

The pump jet. Note the a very

very small washer/gasket accompanies this part and comes with most rebuild kits.

Figure 29. DCOE Accelerator Pump Jet

Back-Bleed/Spill Jet that sits at the bottom of the

fuel bowl

Figure 30. DCOE Accelerator

Spill Jet

Starter Circuit

Drawings

The DCOE Starter Circuit is a Carb

within a Carb. It has its own fuel jet and air jet along with separate passages

in the housing. There are two pistons that are raised and lowered by a cable to

allow the manifold vacuum to draw the fuel/air mixture from the hole in the roof

of the throat. Note: Since the Starter Pistons are on the high vacuum side

of the throttle plate, they can be a cause for fuel leakage. Often they can get

stuck open from carbon deposits.

Figure 31. DCOE Starter

Circuit

Figure 31. DCOE Starter

Circuit (Side View)

Figure 31. DCOE Starter

Circuit (Side & Front View)

Figure 32. DCOE Starter Circuit Exit

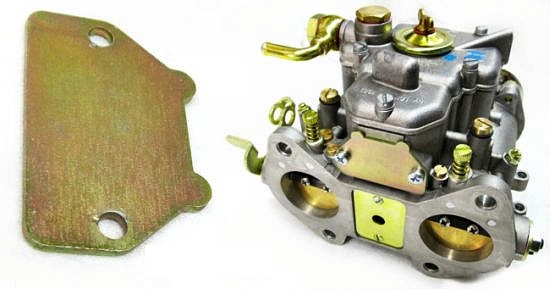

Most DCOE racing application carburetors have blocking plates instead of a Starter Circuit.

Figure 33. DCOE Starter Circuit

Blocking Plates

4. Components

The Carb Body (Size & Type):

Weber DCOE Carbs have evolved as a device over the past 85 years. They come in a

variety of sizes and series/type.

Figure 34. 1931 50DCO

Carburetor and 2016 50DCO

Carburetor

The carbs are identified by the diameter of the throat (in mm), and by the

manufacturing variation. Typical DCOE carbs come in

the following standard throat diameters:

40, 45, 50, & 55. Other throat sizes over the years include 38, 42, 48, 58.

Figure 35. 38DCOE Carburetor

and 55DCO Carburetor

Typical sized carbs for Datsun 240z to 280z with motors

ranging from 2.4liter to stroked 3.4liter range from 40mm to 55mm. The

40mm's make nice street carbs for stock 240z's to 280z's and the 55mm are for racing

applications. A 45mm is a good size to purchase for 280z street applications. It can

cover from 2.8 to 3.4 litres and most additional performance modifications of

these.

40DCOE carbs come a variety of types/variations ("Tipo" in Italian) manufactured

over the years. Variations include number of progression holes (2, 3 or 4),

pattern of progression holes, length of pump rod, progression hole threaded plug

or bronze cap. Here are some Tipos and distinct features:

- 40DCOE-2 (14mm pump stroke)

(float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-4

(14mm pump stroke) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-8

- 40DCOE-9

- 40DCOE-13

- 40DCOE-14

- 40DCOE-15

- 40DCOE-16

- 40DCOE-18 (10mm pump stroke) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-19

- 40DCOE-22

(10mm pump stroke) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-23

(10mm pump stroke) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-24

(14mm pump stroke) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-27

(14mm pump stroke) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-28

(14mm pump stroke) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-29 (10mm pump stroke) (float 5.0mm)

- 40DCOE-30 (10mm pump stroke) (float 5.0mm)

- 40DCOE-31 (16mm pump stroke)

(float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-32

(14mm pump stroke) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-33

(14mm pump stroke) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-34 (

) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-35 (

) (float 8.5mm)

- 40DCOE-38 (16mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-39 (16mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-44 (

) (float 7.0mm)

- 40DCOE-45 (

) (float 7.0mm)

- 40DCOE-62 (16mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-63 (16mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-68 (16mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-69 (16mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-70

- 40DCOE-71

- 40DCOE-72 (18mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-73 (18mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-76

- 40DCOE-77

- 40DCOE-80 (18mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-81 (18mm pump stroke)

- 40DCOE-82

- 40DCOE-83

- 40DCOE-84

- 40DCOE-85

- 40DCOE-86

- 40DCOE-87

- 40DCOE-88

- 40DCOE-89

- 40DCOE-92

- 40DCOE-93

- 40DCOE-96

- 40DCOE-97

- 40DCOE-106

- 40DCOE-107

- 40DCOE-149

- 40DCOE-150

- 40DCOE-151

The 151 type is the current commonly available new stock. It has many desirable

features and no wear. It is now manufactured in Spain rather than Italy. The

factory equipment was relocated in 1992.

When selecting DCOE's for your Datsun ensure all three are of the same type and

ideally of the same vintage. Having a mixed set may not distribute fuel evenly

to the 6 cylinders and cause the car to run rougher. It is important to note

that the quantity, size, and location of progression holes varies between 40DCOE

types so this alone will cause fuel delivery differences and difficulties. Mechanical functioning of

the carbs is equally important to ensure they work identically. Different

throttle plate angles and different lengths of the mechanical arms along with

mechanical slop will prevent correct synchronized functioning of the three.

For the best performance, all three carbs should be identical with no mechanical

slop.

Figure 36. 40DCOE2

Carburetor (Type/TIPO is 2 and stamped on top cover)

Figure 37. 40DCOE107A Stamp

and 40DCOE24 Stamp

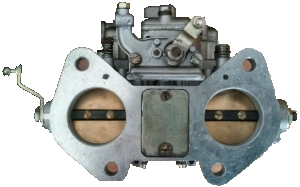

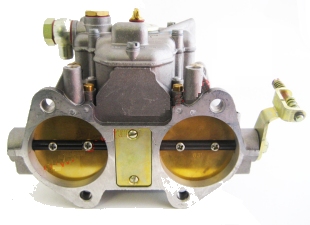

The Venturi (Choke):

The DCOE carb has interchangeable throat restrictors

called Venturi's or Chokes. These devices control the quantity and velocity of

air entering the engine. Generally smaller chokes increase air velocity at low

rpms and improve torque but they eventually become a restriction at higher rpms

and limit maximum power. On the other hand, larger chokes do not work well

at low rpms but they work well at higher rpms. Smaller chokes make street

driving fun. Larger chokes allow race engines to produce maximum power.

Figure 38. A thick-walled

30mm Venturi and a thin-walled 36mm Venturi

Figure 39. Venturi in Carb Throat

After selecting a carb size for your Datsun, the next step is to select a choke

size. 40DCOE's have a choke selection from 28mm to 36mm, 45DCOE's have a choke

selection from 28mm to 40mm, 55DCOE's have a choke selection from 46mm to 48mm.

Common Weber books recommend 40DCOE carbs with 28mm or 30mm chokes for stock

240z's and 260z's.

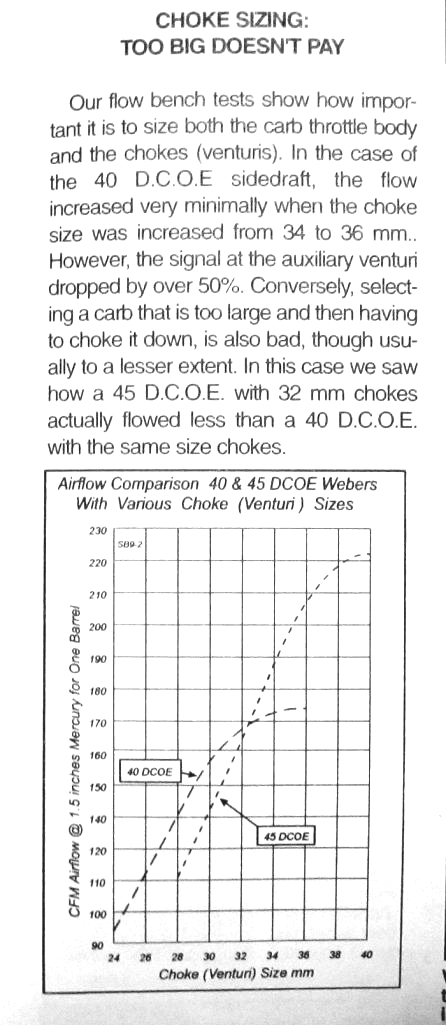

Here is data from flow testing 40mm and 45mm DCOE carbs. It appears that a 32mm

choke is the inflexion point where one should consider choosing a 45mm body over

a 40mm body. This would fit well with 280z 2.8l engines and modified 260z 2.6l

engines. One issue raised by Passini is that the sudden throat diameter change

after exiting a Venturi can be very detrimental to the mixture of air and fuel

as it passes. If the cavity after the Venturi is too large, the mixture will

fail and fuel will precipitate. This condition occurs more in 45mm bodies than

40mm bodies for the same Venturi size.

Figure 40. Plot of air flow in 40mm & 45mm DCOE carbs

vs. Venturi/Choke Diameters

From personal experience, a cam'd 2.4l 240z with 30mm

chokes has a very nice low end torque and works well on the street.

For racing, the smallest choke that gives the maximum power on the dyno is the

one to choose.

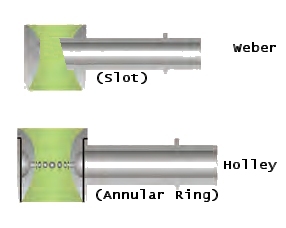

The Auxiliary Venturi:

The DCOE carb has interchangeable Auxiliary Venturi's.

This device is a smaller venturi whose tail is located in the centre of the main Venturi where

the air velocity is greatest and the pressure is least. Its purpose is simply to

expel the fuel from the Main Circuit into the air stream. The fuel is

pulled out of the main circuit due to the low pressure generated by the

Venturi-in-a-Venturi structure.

Figure 41. Auxiliary Venturi (part and installed)

Figure 42. 40DCOE Auxiliary Venturi is just one part.

(The 45DCOE Aux. Venturi is two parts)

Weber Auxiliary Venturi's come in sizes from 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, and 6.0mm.

This size is an "equivalent hole diameter that would flow the same amount of

fuel" as the rectangular slot in the Auxiliary Venturi.

Common Weber books recommend 40DCOE carbs with 4.5mm Aux. Venturi's for stock

240z's and 260z's.

For racing applications, use the smallest size that provides maximum power on

the dyno.

The Idle Jet:

The Idle Jet is inappropriately named as it primarily

controls the cruise mixture more so than the idle mixture. In fact, the Idle

Enrichment Screw directly controls the idle mixture. The Idle Jet simply

feeds it.

When cruising along a street or highway in a Datsun, the Progression Circuit is the main

contributor to the mixture entering the engine. Only the fuel level and

Idle Jet are at play. It is very important to select the correct Idle Jet and

set the correct fuel level in a DCOE carb so that a suitable air/fuel ratio at

cruise is obtained. In the tuning section below, selecting the correct

Idle Jet at cruise will be the first

and most crucial step. The mixture at cruise can not be tuned by the main

circuit nor can it be significantly tuned by the Idle Enrichment Screw.

The cruise mixture must be set by selecting the correct Idle Jet AND by setting

the correct fuel level.

The Idle Jet

Figure 43. Idle Jet and Holder

The Idle Jet mixes air and fuel inside its drilled cavity. Fuel enters from the

bottom and air enters from the side. The air/fuel mixture is drawn out of the

top of the jet and then through four holes in the side of the holder.

The selection of idle jets vary in the following ways:

1. fuel orifice diameter

2. air orifice diameter

3. quantity of air orifices

4. inner cavity diameter

5. top exit diameter

The configuration of the air orifices and inner cavity size determine the

identification of the Idle Jet. They are identified by the letter "F"

followed by a number. There is very little logic to the ID and the combinations.

Examples are F1, F2, F3....

A prefix is added to describe the fuel orifice diameter in 100ths of a

millimeter. A 50F11 idle jet has a fuel orifice of 0.5mm.

The identification of the jet is scribed on the side.

Figure 44. Idle Jet Identification (50F8)

Figure 45. DCOE Idle Jet Selection

Figure 46. DCOE Idle Jet Selection Arranged by

Inlet Area (approximately Richest at the Top)

The Idle Enrichment Screw:

The Idle Enrichment Screw controls the quantity of

mixed air and fuel at idle.

At idle, air is entering the engine at 5 locations (Fig. 47):

1. Around the throttle valve (that is just cracked open).

2. Through the air orifices in the Idle Jet.

3. Scavenged flow into the progression holes.

4. Through Idle Bypass Passage (if equipped).

5. Through holes drilled in throttle plate (if modified as in Fig. 48).

The Idle Enrichment Screw is located at the top of the carb next to the

intake manifold. There is one for each throat. They are visible in Figure 48.

Figure 47. DCOE Air Flow at Idle.

Figure 48. Modified Throttle Plates with

Adjustable Sized Holes.

As mentioned above, the idle jet is first selected to obtain the optimal air/fuel

ratio when cruising. The Idle Enrichment Screw merely tweaks the air/fuel

ratio at idle.

Most Datsuns with Weber's idle best with Air/Fuel ratios of 14.7 or lower.

14.7 would be the cleanest with minimal fumes but at a slight sacrifice of

idle smoothness.

Early DCOE screws had a wide tapered end that flowed more mixture with just slight movements

(turns). Weber later changed DCOE's to a more precise screw with a very narrow taper.

The result is that early DCOE screws flowed adequate enrichment at ~ 1 turn out

from full stop. Later narrow tapered screws flowed the same amount at ~2.5

turns. Current production DCOE151's have the newer, narrower tapered screws.

Figure 49. Idle Enrichment Screws (older, wider

taper on left, newer, narrower taper on right)

The Main Jet, Emulsion Tube, & Air Corrector:

The Main Jet is simply a precise orifice that controls

the quantity of fuel entering the main circuit. It snaps into the bottom of the

emulsion tube. The orifice sizes range from 0.80mm to 2.90mm. The size is

embossed on the jet in thousandths of mm.

Figure 50. DCOE Main Jet Size Selection Table.

Figure 51. Main Jet (part, fitted, flow)

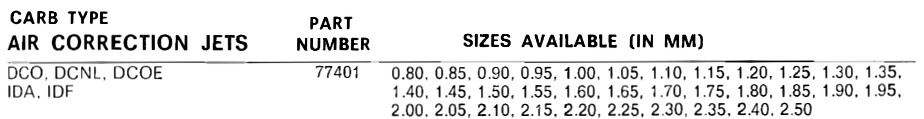

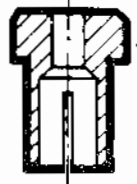

The Air Corrector is simply a precise orifice that

controls the quantity of air entering the main circuit. It snaps into the top of

the emulsion tube. The orifice sizes range from 0.80mm to 2.50mm. The size is

embossed on the corrector in thousandths of mm.

Figure 52. Air Corrector Selection

Figure 53. Air Corrector (part, fitted, diagram)

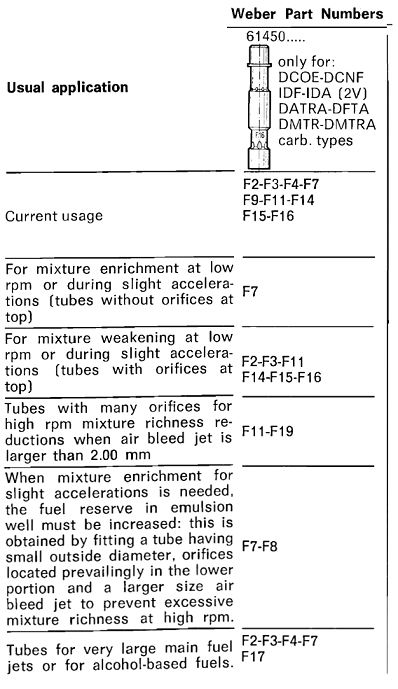

The Emulsion Tube is a complex part that comes in a variety shapes and sizes.

The Emulsion tubes vary by the outside diameter, steps in the outside diameter,

numbers of drillings, diameters of drillings, height of drillings and angle of

drillings.

Its purpose is to mix fuel and air during the acceleration phase from cruise to

WOT. The mixture results from air bubbling through the holes and then into the

fuel flow. The goal is to maintain an air fuel ratio of ~ 12 to 13 across the

acceleration rpm band.

Figure 54 shows the selection of emulsion tubes and typical applications.

Figure 54. Emulsion Tube Selection

The Float, Needle Valve, & Fuel Strainer:

The fuel bowl is centered in the carb body

and feeds both throats.

It is filled through a needle valve. Needle Valves come with different orifice

diameters to cover a wide range of fuel consumptions.

Floats in the fuel bowel rise with the fuel level and close the needle valve

when the bowl is adequately filled. DCOE carbs should be mounted sideways to the

direction of travel so that side-to-side accelerations do not cause the float to

rise or fall (as the fuel sloshes). Fuel starvation at high rpms in a corner can

damage an engine.

The carb body should not be tilted more than 5 degrees when installed so as to prevent fuel leaking into the throat.

The various DCOE "fuel level" settings for different applications (cars) as

often listed in Weber books is to standardize the fuel level such that it

compensates for the tilt of the carb on that particular engine. The common

location for measuring fuel depth is in the emulsion tube well as its proper

functioning is dependent on this level. The typical value is 29mm down from the

top of the well casting. Beware that a commonly touted value of 25mm is often

found on the net but it is too high and leads to running far too rich at cruise

and causes fuel to slosh into the Venturi when the Main Circuit is not active.

Early DCOE floats are made of brass and are hollow. They can develop holes and

sink (causing incorrect fuel levels). Later floats are made from a synthetic

material and are not hollow.

Figure 55. Early Brass Float and Later Synthetic

Float

Figure 55. DCOE Lid (upside down) Showing Float,

Needle Valve, Gasket and Fuel Inlet

Figure 56. Needle Valve and DCOE Lid Showing

Needle Valve, Washer, and Gasket

Figure 57. Needle Valve and Washer (Measuring

height)

Important: Not all Needle Valves and Washers are the same height so this will

affect when the floats shut off the fuel and in turn, affect the fuel level.

Carefully measure fuel level in the Emulsion Tube Well every time the needle

valves are changed.

Figure 57a. DCOE/DCO Accelerator Pump Jet Selection

Figure 58. Fuel Strainer and DCOE Lid showing

Strainer (3) Location (4)

The Accelerator Pump & Jet:

The Accelerator Pump is much like an engine

cylinder. It has a piston, rod, and spring. The piston moves within a cylinder

filled with fuel. When operating, the spring pushes the piston which

squirts a column of gas. The whole assembly squirts in a

downward motion. The spring ensures every squirt is consistently pushed with the

same force. The rod comes in different lengths to vary the piston's sweep and

how much fuel is squirt. The

charge of fuel passes through several internal passages then through the pump jet.

The pump jet exit is on the roof of the throat just in front of the throttle

valve. It squirts over the top of the throttle valve. The size of the Pump Jet

Orifice effects the density of the fuel stream which is squirt and also

contributes to the duration.

As with nearly every other DCOE part, the accelerator pump's rod, spring, and jet

are all interchangeable with a wide selection of variations to make the carb

match the engine and application.

Figure 59. DCOE Accelerator Pump Parts and

Springs

The Accelerator Pump Jet has a very small aluminum washer fitted to ensure a correct fit. It sometimes is overlooked when replacing parts.

Figure 60. DCOE Accelerator Pump Jets and Washer

The Spill Jet, Weight, & Ball Valve:

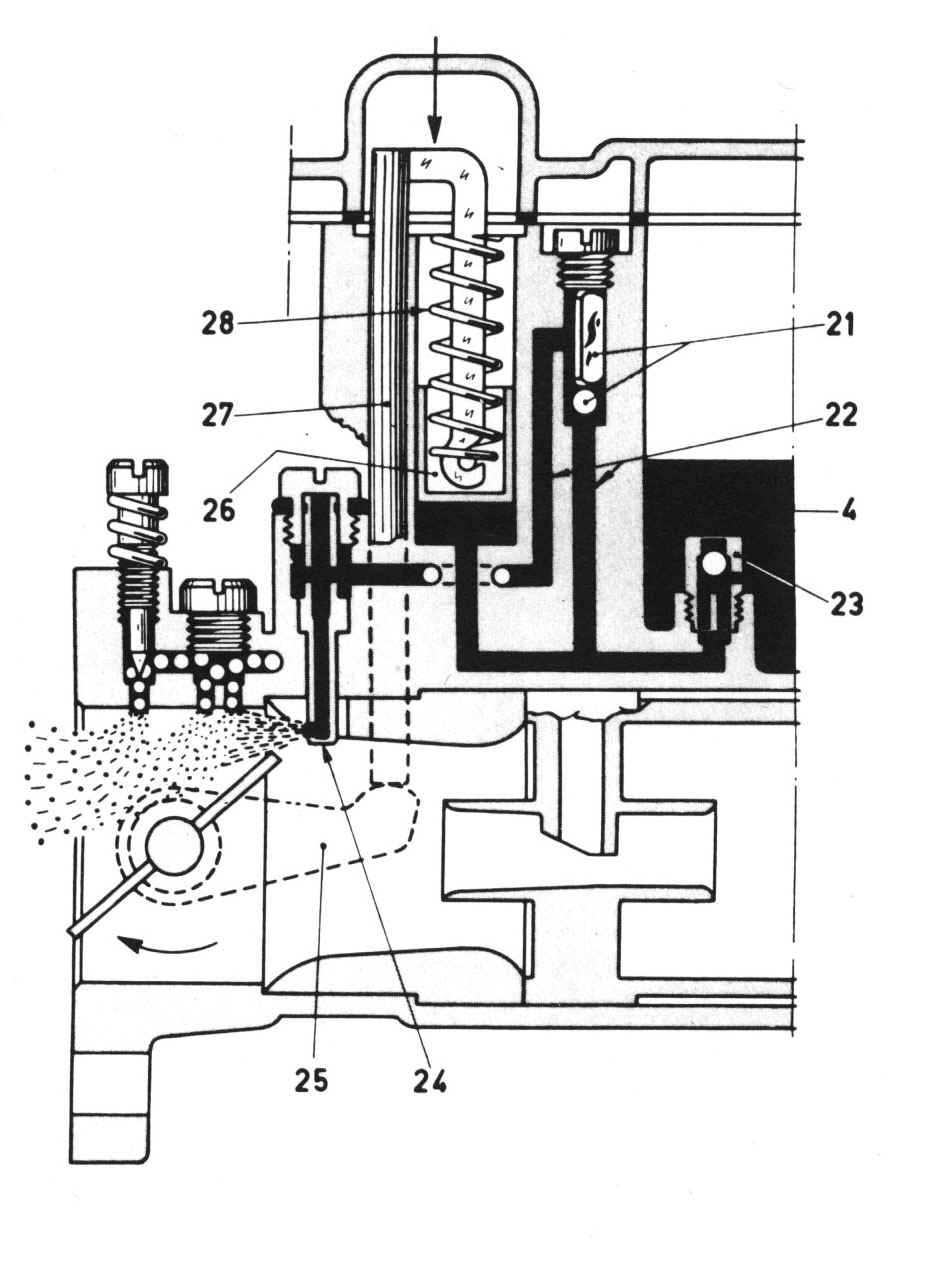

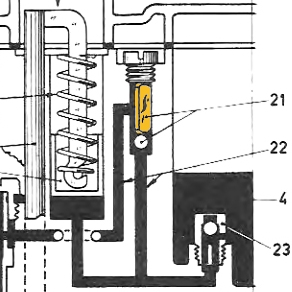

Figure 60a shows the details of the Accelerator Pump Circuit.

The Accelerator Pump Circuit contains additional parts to control when it

squirts fuel into the engine. The accelerator pump circuit is activated (by

lever #25 dropping) every time the accelerator pedal is pressed. It is desired

that circuit dispenses fuel on only on rapid pedal pressing but not on slow

pedal pressing. To facilitate this, the output from the pump piston can travel

two paths: 1. to the engine (fast press through #24), 2. back to the fuel bowl

(slow press through #23). Path to the engine has a vertical passage blocked at

the bottom by a ball (#21)with a weight on top (#22). The path to the fuel bowl

also has a ball valve in a jet (#23) where the fuel returns back to the bowl

(through side of this jet).

A fast press of the accelerator pedal drops lever #25 allowing spring #28 to

push the piston #26 down. The piston pushes fuel from its chamber towards the

ball valve #21 and towards the ball valve #23 (Spill Jet). The pressure of the

push forces the ball valve and weight #21 upward. This opens the passage and

allows the pressurized charge of fuel to continue on to the Accelerator Pump Jet

#24 then out into the engine via the carb throat. The piston also pushes fuel

towards the spill jet #23. The ball in the spill jet is forced upward however it

closes off the top which is the main passage from the fuel bowl #4. This closing

off prevents the piston from pushing fuel back into the fuel bowl so that the

charge goes to the engine. The spill jet has a small hole in the side below the

ball valve thus a small amount of the charge does leak back into the bowl.

A slow press of the accelerator pedal prevents the spring #28 from pushing the

piston #26 quickly. The pressurized charge lacks the sudden impulse of the

spring and is not sufficient to raise the weight and open the valve #21. The

pressurized charge is also not sufficient to raise the ball and close the spill

jet #23, so the fuel is returned back to the fuel bowl through #23.

Fast presses squirt fuel into the engine. Slow presses simply bleed fuel back to

the fuel bowl.

As with all other circuits, the Accelerator Pump Circuit can be matched to the

engine by varying the components. A selection of spill jet bleed back holes and

pump jets are available.

Figure 60a. DCOE Accelerator Pump Circuit

Figure 61. DCOE Spill Jet

Figure 62. DCOE Accelerator Pump Circuit Weights and Ball Valve

Figure 63. DCOE Accelerator Pump Jet Selection

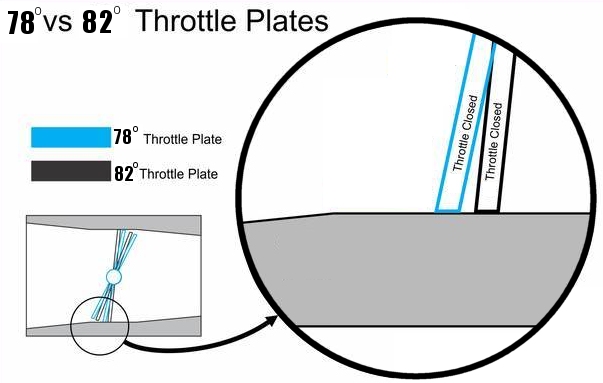

The Throttle Plate:

DCOE throttle plates come in a few variations. They can be used to move the location in

the throat where they come to a close. This relocation can be used to

rehabilitate a carb whose aluminum throat is worn from usage at its original

stop. Altering the throttle plate's stop location also changes distance before

the progression circuit engages. This change may require additional tuning to

compensate.

Some early 40DCOE's came with 78.5°

plates. 42DCOE's had 82°.

40DCOE 78.0° part: 64005.044

40mm 78.0° part: 64005.087

40mm 78.0° part: 64005.126

40DCOE 78.5° part: 64005.059

45DCOE 78.0° part: 64005.084

50DCOE .0° part: 64005.135

Figure 64. DCOE Throttle Plates 78° and 82°

5. Tuning

(TBD)

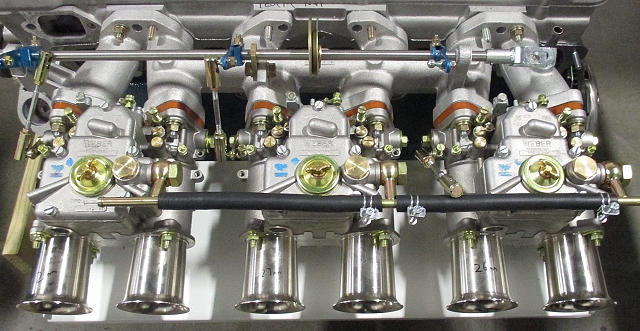

This section is specific to tuning Triple Weber DCOE Side Draft Carburetors on

the Datsun 240z, 260z & 280z. The principals will apply to other applications.

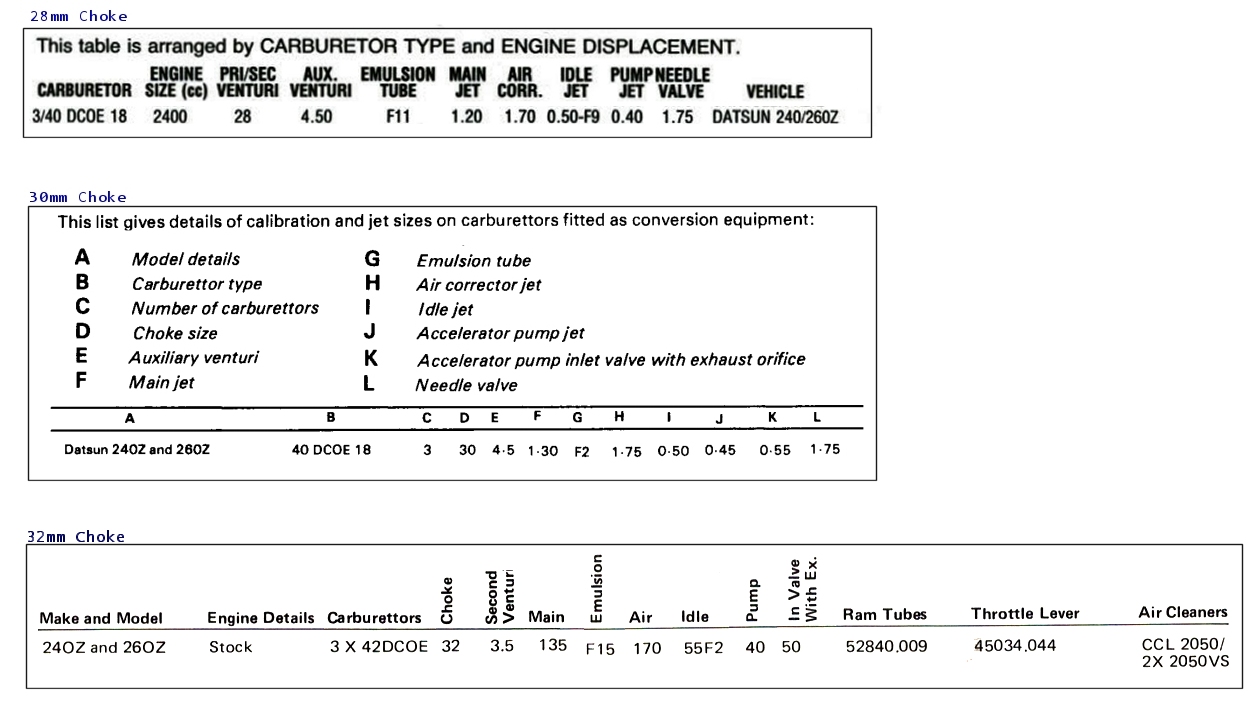

Here are the default settings for DCOE's on 240z's & 260z's that are published

in books. These may be useful starting points for some (note the rare and

expensive 42DCOE):

1. Selection of DCOE Type

Linkage

Timing

Heat Shielding

Valve Adjustment

1. plug inlet jet/ball valve leak back to accel.

circuit at bottom of fuel bowl with bolt.

2. set throttle linkage so that valves are covering

the first progression hole.

3. remove main jets.

4. experiment at low rpms and tune the idle circuit

for idle and low rpm operation (carefully drive around to do this and measure

a/f)

5. install the mains and tune for high rpm and WOT

performance

6. balance a/f at cruise at 60mph and 70mph and at idle

6. install the accelerator circuit jet/ball valve AND

add springs to press the weights down OR replace the weights with springs.

7. adjust the accelerator circuit for fast

RPM transitions

6. Rebuilding

TBD

7. Modifications

Accelerator Jets:

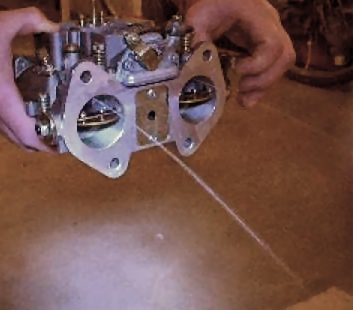

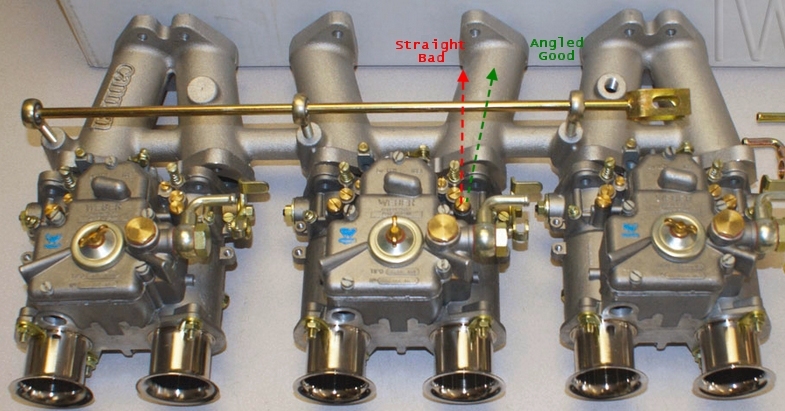

1. Align the "squirt" with the manifold:

File flat section of the accelerator

jet so that it can be clocked such that the "squirt" shoots in the centre of the

manifold runner. This problem arises because the default shot is straight out

the back of the DCOE however, the 240z,260z & 280z manifold runners are angled towards the input

ports on the head.

2. Disperse the Spray:

Drill more holes in the accelerator jet to reduce the large liquid squirt

into a finer misting spray. (Part is available in Japan)

3. Stop Leaking:

Install springs to replace the weights. This will prevent the the accelerator

circuit from leaking due to road vibrations lifting the weight. Springs can be

sourced from pens.

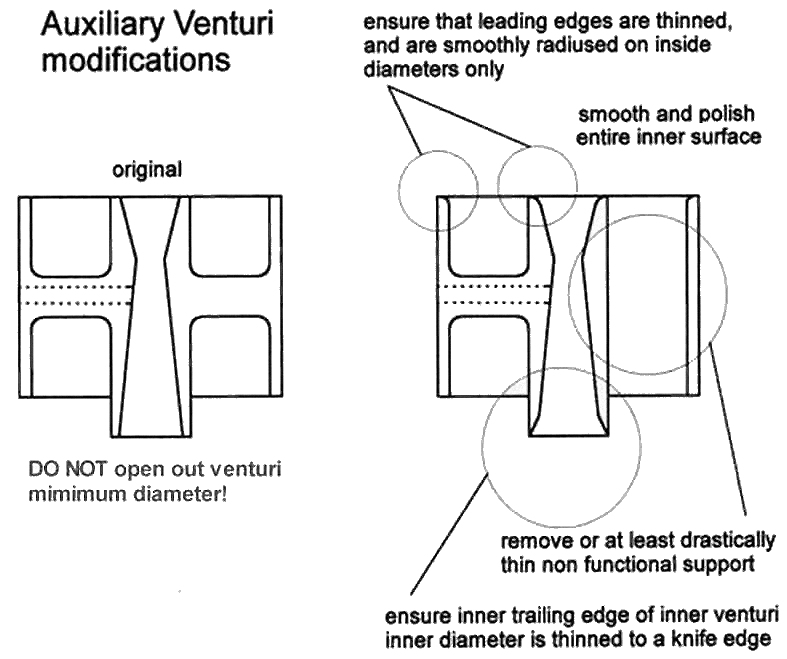

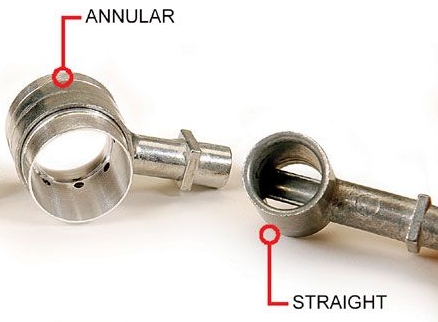

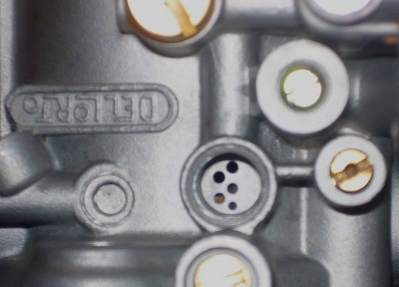

Auxiliary Venturi:

1. Reduce Obstructions:

Remove the structural post side of cross-member so that the Aux. Venturi is

only supported from one side (like Dellorto below).

2. Refine Airfoil:

Shape the leading and trailing edges to reduce manufacturing imperfections

and to improve flow.

3. Improve Aux. Venturi Type:

Replace Aux. Venturi with Annular Discharge Ring insert (like on Holley Carbs).

4. Improve High Rpm Atomization

Slot the upstream and down stream Venturi Tube:

Throttle Valve Shaft:

1. Reduce the cross-sectional blockage:

It is not recommended to thin the throttle valve shaft

(It is already done). Simply countersinking flat-top screws and trimming the

protrusion is all that is needed.

Throttle Plate:

1. Balance Throats at Idle:

For non-40DCOE151 carbs, drill holes in the throttle plate to balance the

idle air between the two throats in a carb. Solder shut if you drill too big.

Below is an extreme adjustable example.

Throttle Plate Return Spring:

1. Improve Throttle Plate Closing (40DCOE):

Install a stronger spring to consistently return the throttle plates to a

fully closed position. This stabilizes idle.

Weber Part No: 47605.012 Normal (Weakest)

Weber Part No: 47605.027 Stronger

Weber Part No: 47605.009 Strongest

Intake Port:

1. Install stubby elliptical shaped air horns that have full radius to the back.

Linkage:

1. Improve Mechanical Precision of Linkage:

Replace conventional rods with adjustable rods.

TBD

Manifold Heat:

1. Increase heat into manifold:

A hot intake manifold will quickly evaporate liquid fuel. Capture heat from head

and from exhaust below.

Carb Insulation:

1. Thermally Insulate the carb:

Insulate the carbs from the intake manifold's heat and from the exhaust header's

heat so they remains cool. A lower heat shield and ducting air from the front of the engine bay helps

to cool the carbs.

Annular Ring Venturi:

1. Replace the Aux. Venturi and Main Venturi with a single Annular Ring Venturi:

Install a "Giant Holley Booster" in the throat of the carb.

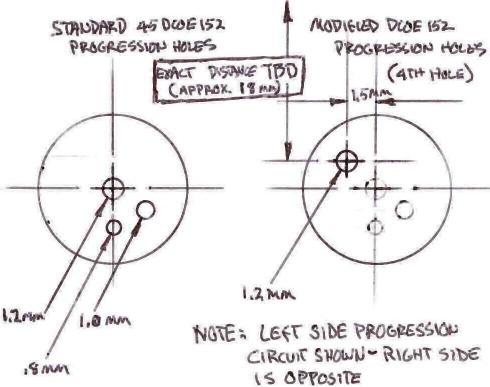

Progression Holes:

1. Drill more progression holes to change progression behaviour.

Notes:

This is for information only. This modification is a

drastic last step and is generally not needed to make DCOE carbs work on a Z.

All jet variations, emulsion tube variations, choke sizes, aux Venturi sizes and

fuel levels should be explored before drilling more holes.

This modification requires accurate hole placement so a drill or milling machine

with precise x/y table is needed.

Some 45DCOE carbs have 2 holes, some have 4 holes, most have 3 as well as most

40DCOE's have 3 holes. FYI many Dellorto's have 5.

Here is an example of a 45DCOE152 (3 hole to 4 hole)) drilling template:

Here is a 45DCOE15 (2 holes) and a 45DCOE152G (4 holes) and Dellorto (5 holes):

8. Racing

1. When towing or transporting a car with Weber

carbs, a dry fuel bowl will allow the float to bounce and jump with every

vibration and pothole in the road. A rubber-tipped needle valve will reduce

wear and tear.

2. Some racers remove and replace the internal

throttle return spring with an external spring as the internal spring may

break resulting in a stuck-open throttle which may cause a fatal crash.

However this modification causes another risk: The locking pin of the

accelerator pump cam can slip away and block the throttle in an OPEN

position because by removing the internal spring, it removes the force on

the locking pin which holds it tight. Without this force the pump cam may

vibrate from engine and road vibrations which will eventually destroy the

pin. In fact it is much more dangerous to remove internal spring then keep

it in place. If someone would like to remove internal spring, then also

remove the pump cam pin and replace it with stainless wire of appropriate

diameter, leave it longer than the pin, and bend it on both ends.

9. Documents

Borg Warner:

-

"Weber

Carburettors A Guide to Tuning"

Centerline:

-

"Set Fuel

Level 29mm"

Hammil:

-

"How to Build and Power Tune Weber DCOE Carburettors" (Text for searching)

-

"How to Build and Power Tune Weber DCOE Carburettors" (Grey Scale Images)

-

"How to Build and Power Tune Weber DCOE Carburettors" (Colour

Excerpts)

Inglese

- "V8 Manifold"

Passini:

-

Excerpts

from "Weber Carburettors Tuning Tips And Techniques, John Passini"

WebCon:

-

"Starter Circuit

Block"

Weber:

-

"Weber Tuning

Manual"

-

"Weber DCOE

Service Manual"